Our beloved aviation industry has always enjoyed the privilege of connecting people. Whether it be for family or business, flying tourists from remote Van Zylsrus to Bloemfontein in a Cessna Caravan or connecting loved ones to New York from Johannesburg in an A340-600, there’s always been that satisfaction as a pilot of a job well done, along with that everlasting camaraderie that connects and identifies us.

Then, as suddenly as the invisible, yet insidious microburst appears with the summer thunderstorms, our industry is reeling through no fault of our own. The almost surreal dichotomy of this global pandemic is that while our industry is designed to connect people, there are forced directives to do the very opposite which has brought our industry and profession to a standstill.

It’s not surprising that this current crisis surpasses 9/11 many times over in terms of the negative impact on our industry. Back then, pilots were initially very pro-active in seeking information and communicating with each other, and while human beings are intrinsically resilient (the ability to cope with adversity), as time went on, many withdrew and began to isolate. Many suffered relationship breakdowns, financial ruin, self-medication through substance misuse and self-harm. It was a time in our history when mental health and wellbeing was poorly understood, least of all acknowledged for perceived fear of medical certification and licensing issues.

Nineteen years on and, while the circumstances differ, similar behavioural patterns are beginning to emerge. At a neuroscience level, our collective brain response has been to enter what is commonly referred to as the “fight, flight or freeze” response, but in our language, we could simply call it “getting stuck behind the drag curve”.

But what does that actually mean and what does it look like? First of all, let’s go back to the neuroscience but keep the theory down at our level. Generally, as pilots, our resilience is amongst the highest in any profession; it defines us as professional aviators. However, when we are faced with a situation outside of our control (as presented by COVID-19) our brain automatically switches into survival mode, which is commonly referred to as a “normal reaction in an abnormal situation”.

In this context, our brains are wired to recognise “threat” and “reward” and we react accordingly. A popular model used in the psychological world is the “SCARF”1 model of human behaviour; which refers to “Status” – the sense of importance relative to others; “Certainty” – the need for clarity and the ability to make accurate predictions about the future; “Autonomy” – the sense of control over the events in one’s life and the perception of influence over outcomes; “Relatedness” – the sense of connection and security with others; and “Fairness” – the just and non-biased exchange between others. COVID-19 presents this model in sharp focus for our profession and, while all attributes are interwoven and the same relative importance, “connection” (or moreover, “isolation”) presents one of our biggest challenges.

Our brain experiences the workplace first and foremost as a social system (Status). It is a social organ; its physiological and neurological reactions are directly and profoundly shaped by social interaction; its designed to “connect”1. When that is taken away from us and deliberate connection (Relatedness) is not maintained through friends and/or family, there is a tendency to isolate (again, this is a “normal reaction to an abnormal situation’).

However, just as the invisible microburst has the capability to do serious harm for the uninitiated, isolation (loss of connection) has just as insidious and potentially more likely harmful impact if not recognised early.

Most of us enjoy a beer or two with mates and in normal situations, it helps us connect; a “social lubricant”. However, during prolonged stressful situations (“getting behind the drag curve”), some people can easily slip into using this social lubricant as a maladaptive coping mechanism, and like the insidious hidden microburst, can easily become a harmful habit which impairs our daily functioning and causes secondary problems or exacerbates existing stressors (eg. Relationship and financial stress). A warning sign is, for example, when alcohol is no longer used moderately within a social context but on one’s own in excessive amounts. The same applies to misusing drugs, prescription or otherwise.

Historically, most pilots who have developed a substance use disorder do not self-refer, either through the perceived fear of reprisal, social stigma or simply a lack of awareness there may be an issue. Often times, it’s not until the pilot is “caught” that the issue is highlighted and then can involve disciplinary and or legal proceedings. It is important to recognise that while elevated alcohol consumption is a “normal reaction to an abnormal situation”; if the misuse of alcohol or other drugs progresses into a disorder, it then presents a flight safety hazard, along with serious social and health complications for the individual. Awareness is key.

What does substance use disorder look like? Or how can I tell if I am drinking too much? Very simply, the key features of substance addiction are the use of drugs or alcohol despite negative consequences and recurrent relapse. Importantly, the issue is not the quantity or even the frequency, but the impact2.

“Impact” refers to the “consequences on your environment”, ie. to what extent it interferes with your daily life and how it infiltrates different areas and aspects of your life. For example, missing your child’s early morning soccer game because you’re sleeping off a hangover, not being able to remember the events of the night before and so on.

Addiction, although a medical condition, is a complex condition in which there is often an interplay between various factors such as the complex interaction of human beings and their environment as well as biological, chemical, neurological, psychological, medical, emotional, social, political, economic and spiritual underpinnings, to name but a few.

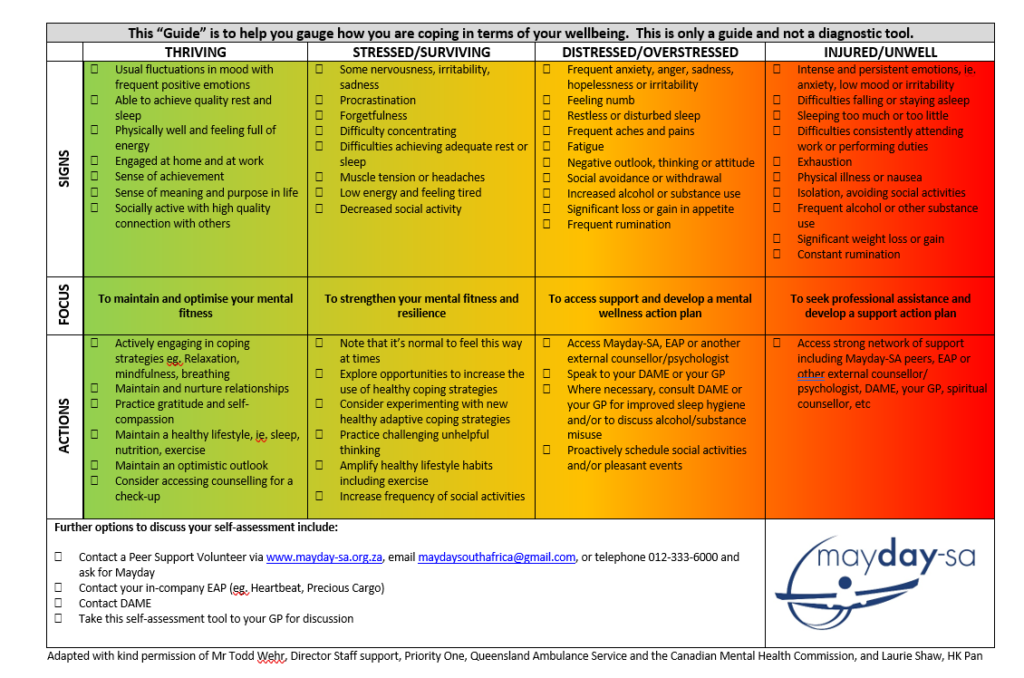

The “self-assessment guide” (included below) is very helpful to gauge how you are coping in terms of wellbeing. Take the time to see where you honestly fit into the continuum; most of us are “flip-flopping” between “stressed” and “distressed”. If you see yourself more frequently into the “distressed” column or even venturing into the “injured” column, reach out in full confidentiality to a peer at Mayday–SA or to your local GP for guidance.

This pandemic is presenting enormous challenges at a global, national, family and personal level. Maintaining connection and looking out for family, friends and colleagues carries a huge positive impact. Your peers at Mayday-SA are always there as a listening ear; especially on the sensitive issues such as alcohol and other drugs.

Written by Laurie Shaw, a Captain with Cathay Pacific Airways, based in Brisbane, Australia. Lauri has worked extensively with key stakeholders in developing systems for pilots afflicted with substance use disorder and is the co-ordinator for the Peer Assistance Network (PANHK).

References:

- David Rock, Strategy + Business, Managing with the Brain in Mind (2009): Neuroscience research revealing the social nature of the high-performance workplace

- Gabor Mate, “In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts”, “What is Addiction”, “A Different State of the Brain” 136 – 51, 386